Robert Indiana

-

Robert IndianaEAT, 2011Screenprint32 x 30 ins 81.28 x 76.2 cmHand signed in Pencil by Robert Indiana.

Robert IndianaEAT, 2011Screenprint32 x 30 ins 81.28 x 76.2 cmHand signed in Pencil by Robert Indiana. -

Robert IndianaMetamorphosis Of Norma Jean, 1998Screenprint35 x 35 in

Robert IndianaMetamorphosis Of Norma Jean, 1998Screenprint35 x 35 in

88.9 x 88.9 cm68/90Hand signed and dated in pencil -

Robert IndianaBook of Love (German colors), 1996Silkscreen24 x 20 ins 60.96 x 50.8 cm

Robert IndianaBook of Love (German colors), 1996Silkscreen24 x 20 ins 60.96 x 50.8 cm -

Robert IndianaKVF !, 1990Silkscreen77 x 53 ins 195.58 x 134.62 cm

Robert IndianaKVF !, 1990Silkscreen77 x 53 ins 195.58 x 134.62 cm -

Robert IndianaSanta Fe Opera Poster, 1976Silkscreen w/foil31 x 22 ins 78.74 x 55.88 cm

Robert IndianaSanta Fe Opera Poster, 1976Silkscreen w/foil31 x 22 ins 78.74 x 55.88 cm -

Robert IndianaART Rainbow SilverSilkscreen print29 1/2 x 33 ins 74.93 x 83.82 cm

Robert IndianaART Rainbow SilverSilkscreen print29 1/2 x 33 ins 74.93 x 83.82 cm -

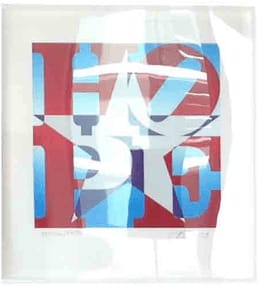

Robert IndianaHOPE Red Blue Silver RainbowSilkscreen print29 1/2 x 33 ins 74.93 x 83.82 cm

Robert IndianaHOPE Red Blue Silver RainbowSilkscreen print29 1/2 x 33 ins 74.93 x 83.82 cm -

Robert IndianaHOPE Red Silver Purple BlueSilkscreen print29 1/2 x 33 ins 74.93 x 83.82 cm

Robert IndianaHOPE Red Silver Purple BlueSilkscreen print29 1/2 x 33 ins 74.93 x 83.82 cm

On May 19, 2018, the day before Robert Indiana died, a New York-based copyright holder filed a lawsuit, accusing Indiana’s caretaker and a New York-based art publisher of taking advantage of the artist. A settlement was reached a few weeks ago that could open the way for Indiana’s Maine island home to become a museum.

Millions of dollars have been spent on litigation in the past three years related to Indiana’s estate, causing the state attorney general’s office to demand an accounting of the estate’s spending.

The bickering is a far cry from the LOVE icon that Indiana created in 1965 for a Museum of Modern Art Christmas Card.

After his death, at age 89, the curators at the Smithsonian went through their archives and found, among other things, touching stories of the life of the shy, seclusive artist. They also uncovered an early version of the Christmas LOVE card, which he sent to Dorothy Miller, the Museum of Modern Art’s curator in 1964, the year before he was commissioned to create the design for the card that became an icon.

Indiana began to get recognition in 1961, when, after a show in which he didn’t sell a thing, MoMA founder, Alfred Barr, walked into the gallery and bought The American Dream for the museum. In 1965, MoMA commissioned Indiana to design a Christmas card. He submitted the LOVE design, which is still used throughout the world on mugs, sneakers, postage stamps and many, many other surfaces.

“I’m a father to a bad child,” he says of the LOVE design, “It bit me.” Although it’s what he’s best known for, and is so ubiquitous, the LOVE design cards were never copyrighted. Indiana was told that he couldn’t copyright a word. “It’s difficult to talk to the Copyright Office,” he said, “they are just as pleasant as the IRS.”

His love-hate attitude toward the LOVE design is understandable. Indiana is a highly skilled artist. His crisp lines and fine designs make him an American treasure, but much of his work is relatively unknown.

Indiana was born on September 13, 1928 in New Castle, Indiana. He was adopted, as an infant, by Earl and Carmen Clark. They named him Robert Clark, but he changed his surname to, “Indiana” in the 1950s. The family moved around a lot in because, Indiana said, his mother was looking always looking for a better house. “I lived in 21 different houses before I was 19 years old,” he said. He attributes his fascination with numbers to the many addresses, streets and routes he came in contact during his childhood.

Indiana created many amazing projects during his career, including a floor for the Mecca basketball stadium in Milwaukee in 1977. It was the first floor in NBA history to have every square inch covered in design. The Bucks made the playoffs in 13 of the next 14 seasons playing on that floor.

In 1988, the Bucks moved to a new arena… and didn’t take the floor with them. The city tried to sell the floor and couldn’t. Storage of a piece that large was a problem, so it was eventually sold to a salvage company. It was rescued by a Milwaukee family, but is still looking for a home. The story of the floor and Indiana’s part in trying to save it, is told in a short film, called, “MECCA: The Floor That Made Milwaukee Famous.”

Indiana’s parents divorced in 1942. He lived in Indianapolis with his father so that he could attend the art program at Arsenal Technical High School. After graduation, Indiana served in the Air Force. The G.I. Bill enabled him to attend the Art Institute of Chicago, spend a summer at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and then go on to a year of study at the Edinburgh College of Art.

When asked about his influences, Indiana names the Kitchen Sink Artists, like Gerald Murphy, and his friends Ellsworth Kelly and Cy Twombly. He also mentions, ironically, Alec Guinness, in the movie, “The Horse’s Mouth,” based on the novel by Joyce Cary. Guinness wrote the screen play and also played the leading role of Gulley Jimson, an eccentric artist…a bit like Indiana himself.

In 1956, Indiana moved to a studio in the south port of Manhattan called the Coenties Slip. There, surrounded by artists, including Ellsworth Kelly, he made some of his best and most creative work. When his lease ran out in 1978, he moved to Vinalhaven.

Much of Indiana’s work comes from his personal life and and some of it is political, like Yield Brother, which he donated to the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation.

-

Lucy Sparrow's Deli. En Imamura's New Studio

A New Book About the Artists of Coenties Slip October 10, 2023Lucy Sparrow’s (b.1986) third solo show in New York is on exhibit now. It is as unique, entertaining and fun as all of her previous...Read more -

Recent Acquisitions at VFA

Works by Alex Katz, Helen Frankenthaler, Robert Indiana and Donald Sultan October 4, 2023This has been a banner year for Alex Katz . His retrospective at the Guggenheim was a huge success. Katz had other successful solo shows...Read more -

Yoshitomo Nara and Roy Lichtenstein at Albertina Modern

VFA at Art on Paper September 7, 2023Many people say that these are children but I think these are not children that I paint. Therefore, they are no particular children but for...Read more -

Carmen Herrera and Ellsworth Kelly Exhibits

March 29, 2023In 2021, the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas in Austin, commissioned Cuban-American artist Carmen Herrera to create a mural for the...Read more -

Robert Indiana: In Miami, Selling MECCA

September 7, 2017The works of Robert Indiana , and many other great mid-twentieth century artists, will be on display at the University of Miami's Lowe Art Museum...Read more