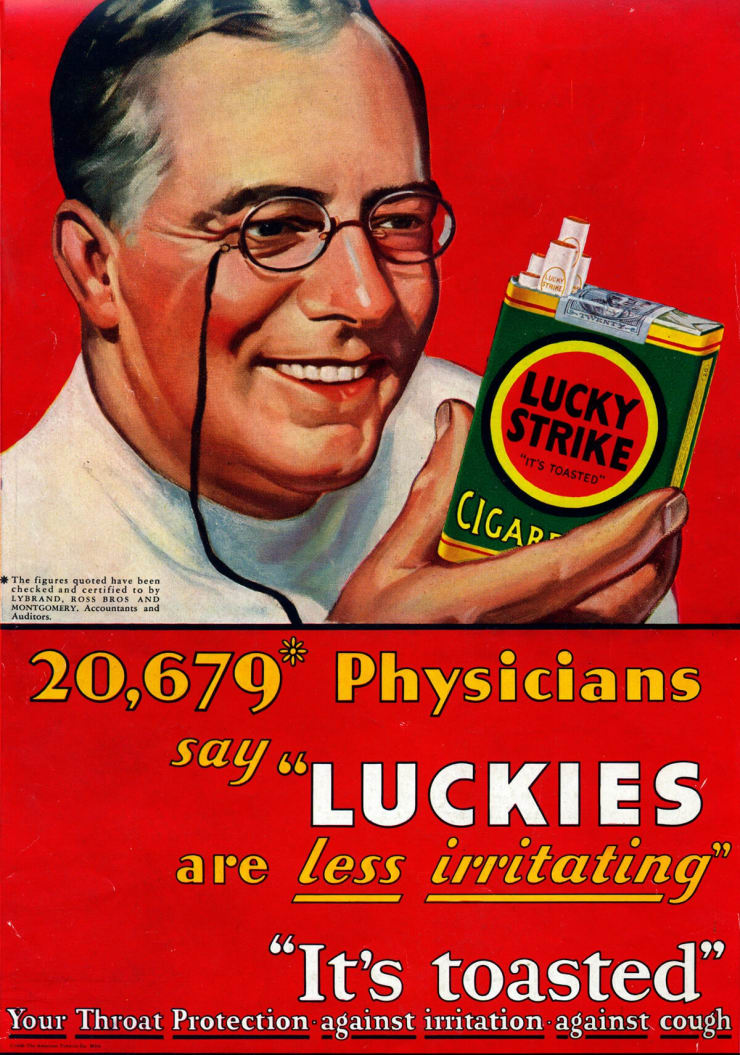

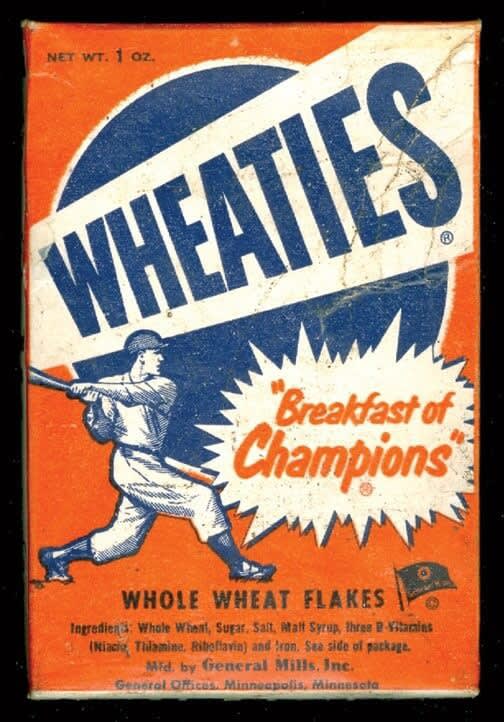

Even for Andy Warhol collectors, who know his enormous body of work, it's hard to separate Andy Warhol from Campbell's Soup and almost impossible to walk down the soup aisle of a grocery store without making the connection. Could Warhol have painted a box of Wheaties or a pack of Lucky Strikes and gotten the same emotional response that he achieved with Campbell's Soup Cans?

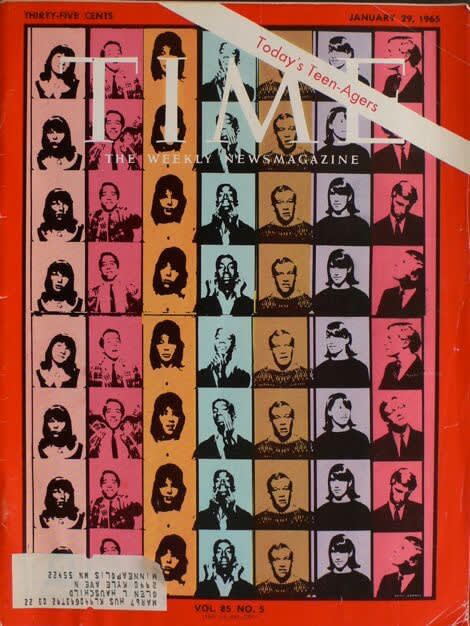

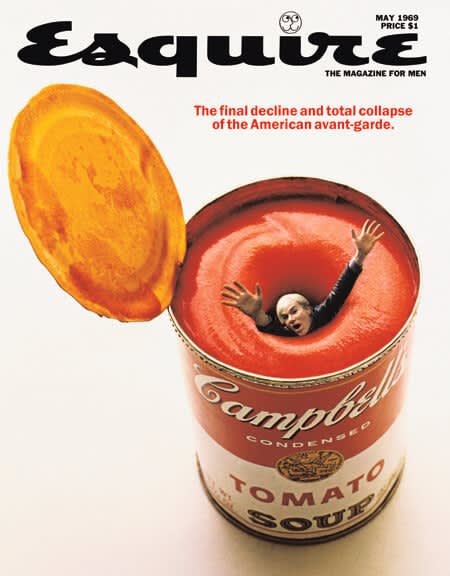

The initial reaction to his paintings of thirty-two Campbell's Soup Cans ranged from indifference to outrage. A snarky review, in the May 1962 issue of TIME magazine, questioned the artistic merits of the works of Wayne Thiebaud, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist and Andy Warhol.

"Unknown to one another," it read, "a group of painters have come to the common conclusion that the most banal and even vulgar trappings of modern civilization can, when transposed literally to canvas, becomes Art." That review was written just a few months before the Los Angeles Exhibit of his thirty-two Campbell's Soup Can paintings…and a few years before TIME magazine began to ask Warhol to design many of their covers.

I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again."

-Andy Warhol (about Campbell's Soup)

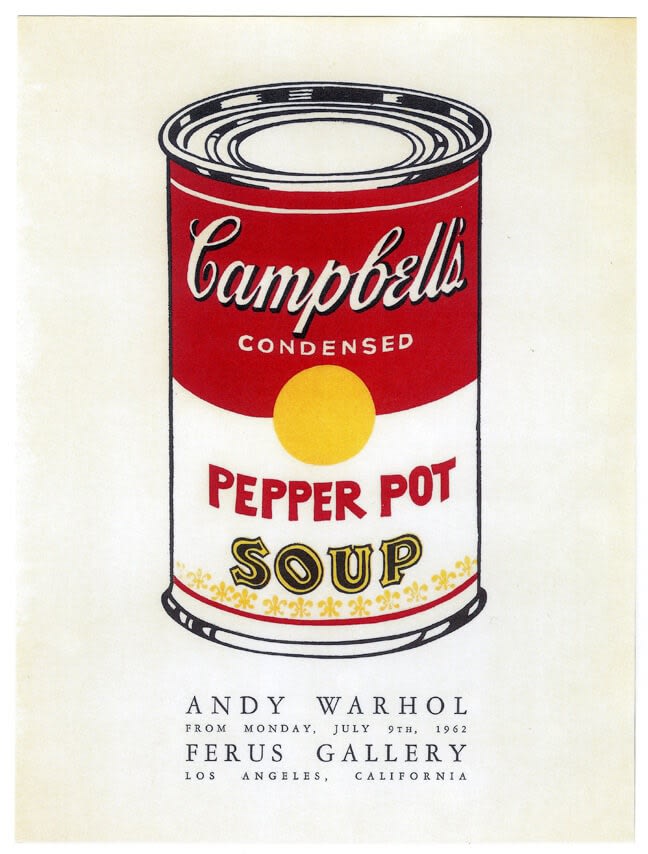

How the derision of the Campbell's Soup Cans turned to admiration, began after the failure of the west coast show. Irving Blum's Ferrus Gallery, in L.A., was struggling, and he wanted to infuse the energy of some New York artists into his exhibits. He visited Warhol in his studio, when only three of the thirty two paintings were completed. Blum convinced Warhol to finish the set and exhibit them in L.A.

Five of the thirty two paintings were sold, one to actor Dennis Hopper, but Blum wanted to keep them all together and bought back all five. He paid Warhol $1000, a payment of $100 a month for ten months, for the entire set. The paintings were acquired by MoMA, in 1996, for $15 million.

The Campbell's Soup Company opened their first factory in Camden, New Jersey in 1896. Canned foods became very popular with people moving to industrialized cities, who didn't have ready access to farm produce. The Depression and war time created a market for both inexpensive food and food that could be transported to troops without spoiling.

For families like the Warholas in Pittsburgh, and, probably, the Blums in Brooklyn, soup was an easy and inexpensive way to feed a family and became "comfort food" for many of their generation.

Julia Warhola, Warhol's mother, had three sons to feed while her husband was away on construction jobs. She used the tin cans to make flowers, which she sold to supplement the family's income. "I used to drink it." Warhol said about Campbell's Soup. "I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again."

The Campbell's Soup labels that are so instantly recognizable today were designed in 1898, when a company executive went to the annual Cornell-Penn football game, loved the red and white Cornell uniforms, and convinced the company to use the colors on the soup can labels.

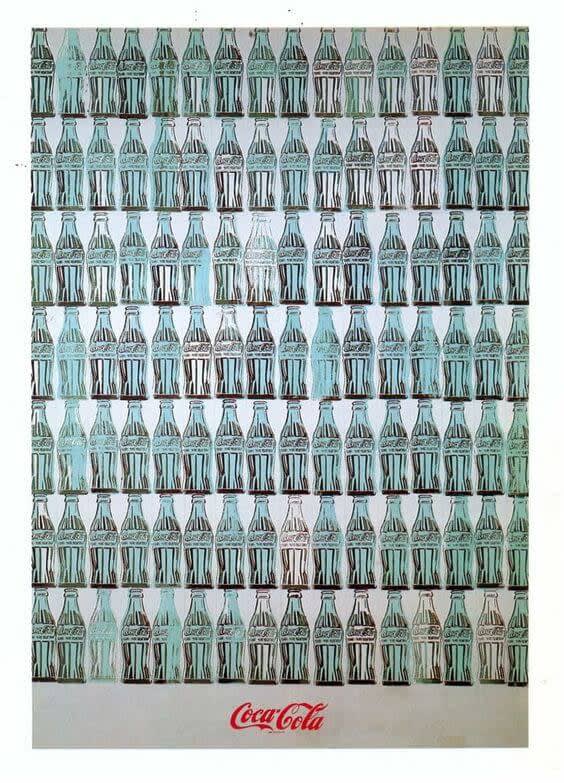

Warhol did paint Coca-Cola bottles, and it would be hard to find anyone in this country, or anywhere else on the planet, who hasn't had a Coke, but it's the Campbell's Soup Cans that still resonate with Warhol fans.

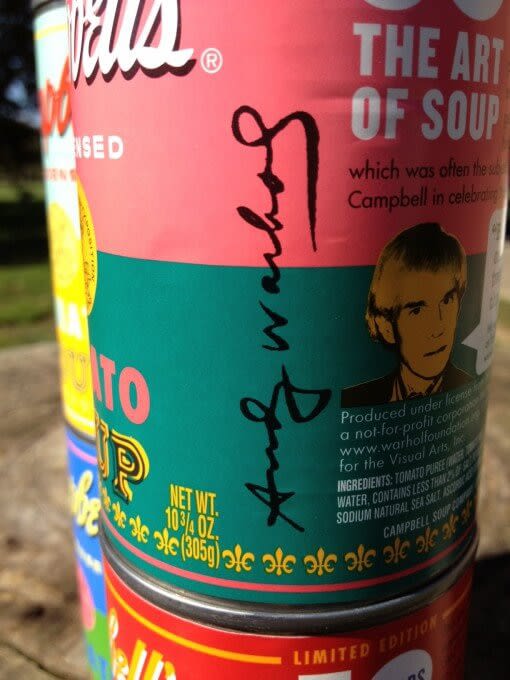

The Campbell's Soup Company issued a limited edition tribute labels to Warhol in 2004, 2006 and 2012, with a printed signature on the side of the can. Warhol had no formal relationship with the company, but they certainly had a symbiotic one.

So, could Wheaties or Lucky Strikes have resonated through the art world in the same way that Campbell's Soup did? Probably not. Most of us probably feel some nostalgia when we think about Thanksgiving Green Bean Casserole with Cream of Mushroom or a bowl of Tomato Soup on a cold winter day.

We invite you to visit our gallery to view Chicken and Dumplings and the other flavors of Andy Warhol.