Robert Rauschenberg’s Monogram opened the door for his contemporaries, like Andy Warhol, to do more than place paint on canvas, ink on paper or a chisel to stone. Rauschenberg was a young artist in New York, in 1955, when he saw a stuffed angora goat in the window of a used office furniture store. The store owner was asking $35 for the goat. Rauschenberg only had $15 in his pocket. Rauschenberg took the goat, and promised to return with the rest.

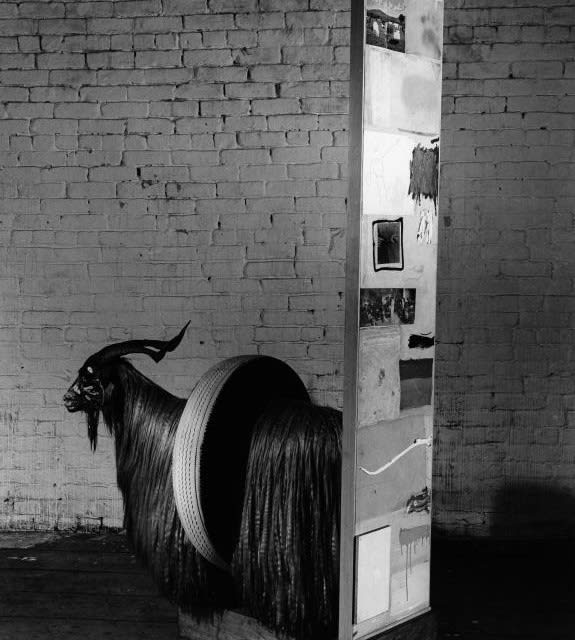

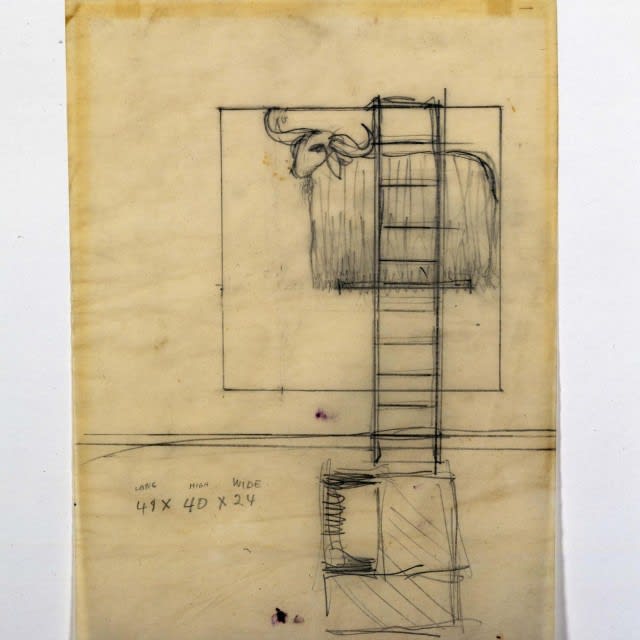

He took the goat home, wrapped a tire around it and worked on the piece for the next four years. When it was completed, it was exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery. Nothing quite like it had been seen before, and it was the subject of much controversy.

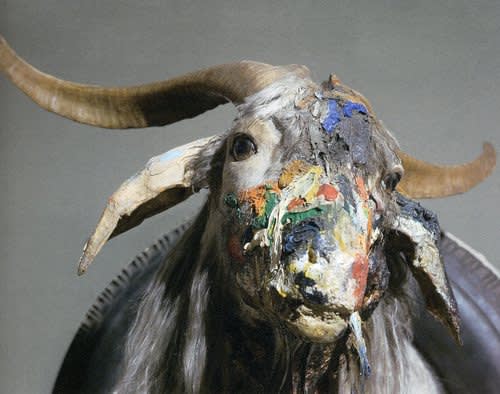

The goat and the tire are entwined, like the two letters of a monogram.The goat’s face is covered in paint and the goat itself is trapped within the tire. Both the goat and the tire are discarded items. “I think a painting is more like the real world if it’s made out the real world,” Rauschenberg said.

When he went back to the office furniture store, to pay the owner the twenty dollars he still owed for the goat, he found the store closed and out of business. A private collector offered to purchase Monogram for MoMA, but Alfred H. Barr, MoMA’s director (and someone who was usually on the cutting edge of the art scene) declined the offer. It was purchased by the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and, over the years, has traveled throughout the world to be displayed in major galleries and museums.

I think a painting is more like the real world if it’s made out the real world”

—Robert Rauschenberg

The base of Monogram, on which the goat stands, is one of the Combine paintings that Rauschenberg worked on during the late ‘50s, combining materials, techniques and subjects.

While abstract expressionism was still shown in galleries at the time, Rauschenberg’s Monogram and Combines allowed the mixed media work of Jasper Johns, and others, to gain greater acceptance.

In 1962, Rauschenberg visited Andy Warhol’s studio and was impressed by Warhol’s silkscreened paintings. Rauschenberg went back to his studio and began to produce silkscreens, like Statue of Liberty, which is in our gallery at this time. We also have fine examples of Rauschenberg’s mixed media work, which he continued to produce until his death, in 2008, at age 83.

Rauschenberg was the first American to be awarded the Venice Biennial Grand Prize in 1964. Art Critic, Jorg von Uthmann, said, “The Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano deplored the event as ‘the total and general defeat of culture.” If you take a look at Monogram from the rear, it’s possible that the goat…but more probable that Rauschenberg…had the last laugh.