Transparent on Canvas

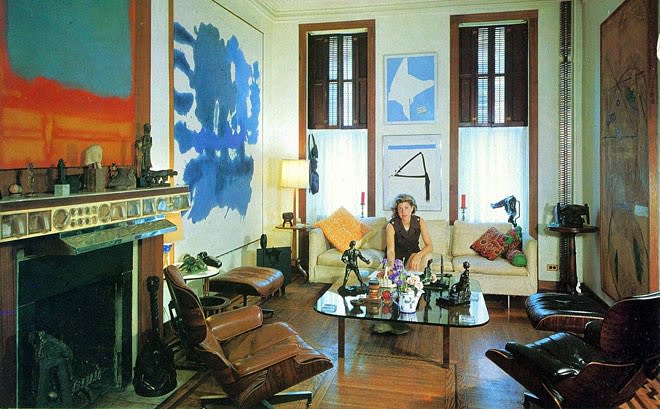

Helen Frankenthaler’s unique innovations with paint and canvas bridged the gap between Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting.

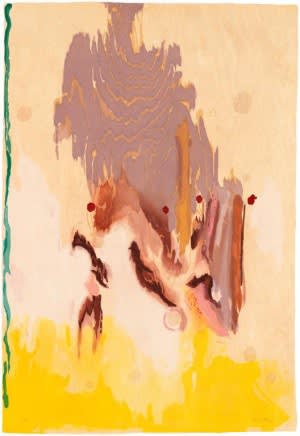

Her technique of using oils diluted with turpentine directly on very large, unprepared canvas, created a field of transparent color. The effect produced intriguing, water color-like, diaphanous sweeps of color that carried with them little evidence of a brush stroke.

In 1953, art critic Clement Greenberg brought artists Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland to Frankenthaler’s New York studio to show them Mountains and Sea. Louis was inspired by the work and called Mountains and Sea “the bridge between Pollock and what was possible.”

Frankenthaler was not just concerned with color, but also with the gestural and spontaneous quality of her work. “A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once.” she said, “It’s an immediate image. For my own work, when a picture looks labored and overworked, and you can read in it – well, she did this and then she did that, and then she did that – there is something in it that has not got to do with beautiful art to me. … I think very often it takes ten of those over-labored efforts to produce one really beautiful wrist motion that is synchronized with your head and heart, and you have it, and therefore it looks as if it were born in a minute.

‘What concerns me when I work, is not whether the picture is a landscape, or whether it’s pastoral, or whether somebody will see a sunset in it. What concerns me is – did I make a beautiful picture?”

The Tough Side

During the 1950s, the New York art scene was pretty much an all-boys club, and Frankenthaler had the determination and toughness to promote her work.

She had met Clement Greenberg when she was at Bennington College and asked him to see her work at a New York gallery. Greenberg agreed to attend the exhibit…if there was booze. Her long association with him was her entrée into the New York art scene. Frankenthaler’s career began with her first major exhibition in 1950 and continued until her death in 2011.

Last year, the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills hosted an exhibition of Frankenthaler’s work. The exhibit was curated by John Eldrfield, the former chief curator of MoMA, who recounted, in a Los Angeles Times interview, how he came to meet Frankenthaler and, eventually, write a book about her.

“My first contact with her was after I’d done a show of fauvism at MoMA.” Elder field said. “She left a note at the information desk saying, “Just saw your show. It was so wonderful, would love to see you.” A couple of days later, the phone rings. It’s Helen Frankenthaler. She says, “Did you get my note?” I said, “Yeah.” She said, “And you didn’t think to call me?”

‘She invited me to her studio for a drink. She said, “I just finished reading your catalog for the show. I don’t suppose you would want to write a book about me?” I said, “I have a day job. I can’t do this.” But 10 years later, that’s what I was doing.”