Our brains are hard-wired to take comfort in symmetry and to look for balance in asymmetry. We humans are constantly looking at the world and trying to make sense of the things we see. We look for order, rather than chaos, in our world, and balance helps to turn that chaos into order.

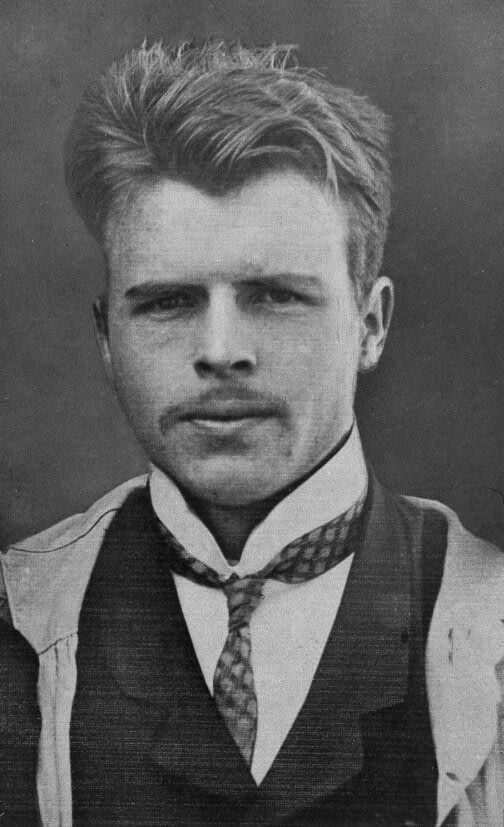

In 1921, Swiss psychiatrist, Hermann Rorschach (who, by the way, looked a lot like Brad Pitt), developed the inkblot Rorschach Test. He showed his patients ten symmetrical inkblots and asked them to tell him what they saw. He then used his patients’ responses as an analytical tool to assess their mental status.

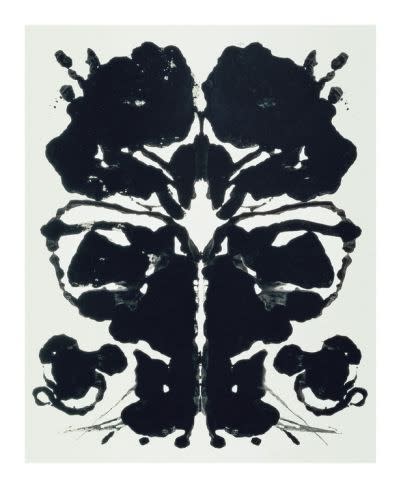

Andy Warhol created his own series of Rorschach Tests, although he misunderstood Rorschach’s method, and thought that the patient created the inkblots and the psychiatrist interpreted them. Warhol’s work, in spite of being Pop, and controversial at times, was mostly symmetrical.

While symmetrical art is visually comforting to us, asymmetrical art is lively, and can even be discomforting, challenging us to seek balance. Both symmetrical art and asymmetrical art need to be balanced to make them complete and aesthetically pleasing.

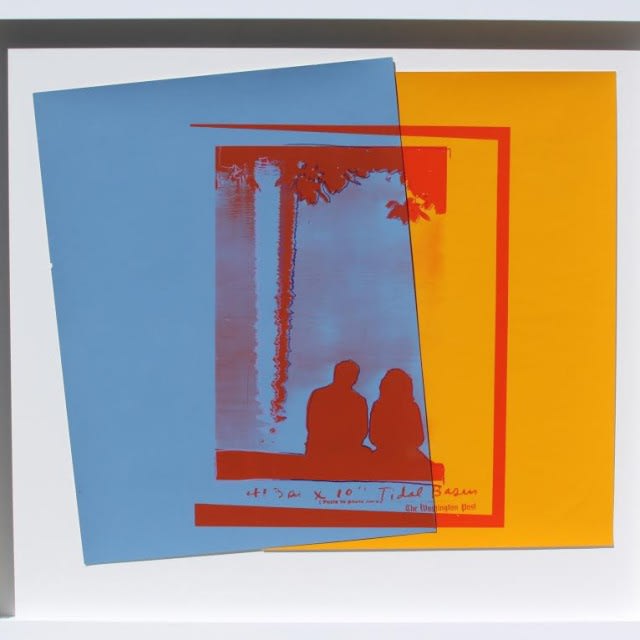

In Warhol’s asymmetrical work, Tidal Basin, Washington Post, Warhol balances the off-centered figures and unfinished frame by tilting the background panel to the left.

The same sort of asymmetry can be seen in the photographs of Elliot Erwitt. Although Erwitt often uses symmetry in his work, like the trees in Provence, he also uses asymmetry to create a sense of movement.

The figures, and their reflections, on the right hand side of Erwitt’s Paris create a balance for the jumping figure in the photo. The formal symmetry of the Eiffel Tower in the background is a perfect counterpoint to the joyful asymmetry of the figures. Erwitt’s use of light and dark forces the viewer to follow the movement across the photo and then look behind and around the figures to make sense of the scene.

The symmetrical faces of our caregivers, that we learn to identify at birth, are usually the first source of comfort we recognize and relate to. Although faces are not usually perfectly symmetrical, we are still able to recognize the facial features and identify the individuals to whom they belong.

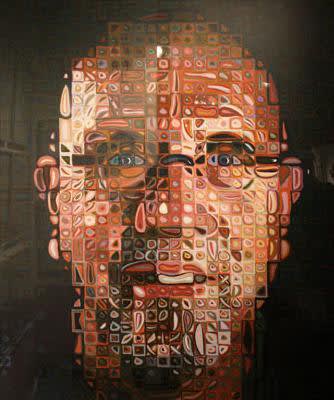

Portrait artist, Chuck Close, is unable to recognize faces, because of a condition called prosopagnosia or face blindness. He has painted faces for most of his life, and creates elaborate portraits by breaking the faces down to two-dimensional photographs and then breaking them down further into small segments. Looking closely at a Chuck Close portrait does not make the face recognizable. Stepping back from the portrait allows recognition.

For a better understanding of face blindness and how it has influenced the work of Chuck Close, check out the video in this post of a discussion that Close had with the late neurologist, Dr. Oliver Sacks, who also suffered from face blindness.

There are many tools that can be used to create balance in a work of art. Balance can be achieved through design, color, shape, texture and form. Painters, printmakers and sculptors all strive to achieve works that feel, to them, complete and balanced.

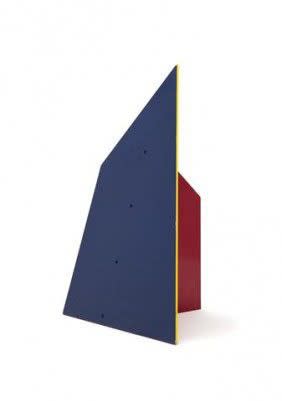

Lyman Kipp created pieces that are asymmetrical and many, at first glance, appear unstable. Through the use of strong lines, colors and materials, he forces the viewer to look up, down and around his sculptures to figure out how the various parts relate to one another and how they maintain their stability. It is the viewer’s perspective that brings the balance to a work of asymmetrical art.

There is no judgement in symmetrical art or asymmetrical art. One is not better than the other. What we bring to our appreciation of a piece of art is our personal history: what we have come to appreciate, our associations with the art or artist and our visceral reaction to each work.

One of the most wonderful things about having a gallery like Vertu, is that we offer the works of our favorite artists, the works that speak to us, and to our clients. Please call, or visit the gallery, to see the pieces above and the many other fine art works at Vertu.